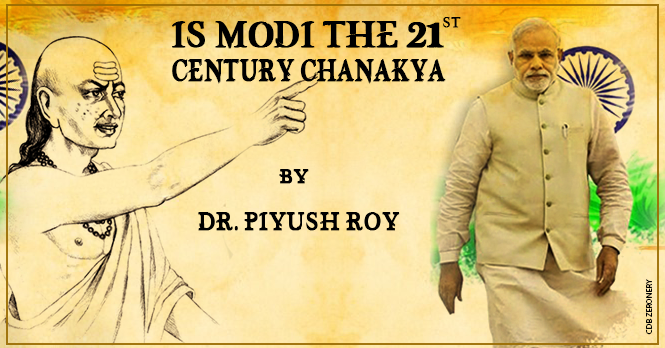

Is Modi The 21st Century Chanakya

Is Modi The 21st Century Chanakya

That the Prime Minister of India is often perceived and portrayed as the most important arbiter of the Indian nation’s destiny isn’t an idea seventy years old, or post-independence only. It is a political tradition and acquired people comfort carried from centuries of monarchies. Hence, it is natural for us to expect in our next Prime Minister an all-powerful, multi-talented, one-person solver of myriad problems.

India continues to draw its ideal ruler references from Valmiki’s Ramayana or Chanakya’s Arthashastra, and not Plato’s Republic. But while expecting a Rama to lead us, are we like the citizens of the idealised Rama Rajya? Rama’s Yuga was Treta (still an age of Virtue), ours is Kali (the age of Conflict). Today’s Prime Minister aspirants are better guided to draw their strategies from a prime-minister achiever from our age of the Kali – Chanakya (371-283 BCE), a philosopher, economist and chief advisor to two Mauryan kings, Chandragupta and Bindusara – and arguably the Indian sub-continent’s most influential and still revered Prime Minister before the advent of modern democracy in 1947.

Politics is not the playing field of the idealist because the nature of its calling is as compromising as it is challenging. That seeking and consolidating power is not an ignoble pursuit and that good governance cannot happen without good economics is nowhere better celebrated than Chanakya’s signature legacy-treatise, the Arthashastra. Using an ‘ends justifying the means’ analogy, the Arthashastra argues that the goal of a welfare state can be achieved only through economic governance, for which political governance is the means. The businessman-politician nexus hence, is not an anomaly, but an opportunity for creating a welfare state, provided that its driven by able leadership and noble intentions from both sides.

Chanakya was as much admired for his political wisdom and statecraft as reviled for his ruthless means towards the end achievement of a powerful and secure Indian state (with Magadha at its centre). Saam (patiently cajoling an adversary to your point-of-view), Daam (persuasion through gifts or material wealth), Dand (the fear of punishment), and Bhed (the threat of brute force) – are the survival and success strategies in a Chanakyan state. Is the scenario any different today?

Can one remain saintly, in a pursuit calling for mastery in the above necessary skills? Any motivation at whose core is the preservation of a material entity – for example the nation and the people within its borders as in politics – the means cannot be always ideal. Also, we have to understand that because of our centuries of conditioning towards a monarchical system of governance, our expectations from our democratic heads-of-state are far different from that of the democratic head in a western model. We are still expecting our PM to be the ‘benevolent dictator’ as described and desired for in the Arthashastra.

Chanakya’s ideal state had seven stakeholders – the king (raja or swami), the ministers (amatyas), the territory with the people in it (janapada), the capital (durga), the treasury (kosha), the army (danda) and the ally (mitra). But the king lorded at the top and is identified ‘with and as’ the state. A strong centralised governance is argued for, wherein a ruler is expected to administer justice on the four principles of – righteousness, evidence, history of customs and prevalent laws. No wonder, even in the 21st century, Indian audiences and critics applauded, and found it perfectly natural when the noble monarch Amarendra Bahubali or regent queen Shivagami, said, ‘Mera vachan hi hai sashan’ in the record-breaking Bahubali film series.

Chanakya hence, gives tremendous importance and impetus to the grooming process of the king-leader, and Chandragupta Maurya’s rise from an able local leader to India’s first ‘Bharat-building’ ruler is a testimony to that. But Maurya was an idealist who perhaps wasn’t cut out for the ‘saam, daam, dand, bhed’ operating principles of politics because of which he retired in his early forties and became a Jain muni. He was at frequent odds with his guru and Prime Minister Chanakya’s ‘unprincipled tactics against those who undermine social order’.

In Chanakya’s BCE 3rd Century prime ministerial calling, there lies another important learning for his 21st century counterparts – never leave without grooming a successor. Chanakya lived in a time of constant intrigue, and he was aware that wielding great power came at a great personal risk. Playwright Vishakhadatta’s Mudrarakshashas offers an intriguing insight into Chanakya’s statesman like vision for his motherland’s long-term security, when he employs every trick, fair and fowl, to get the able amatya Rakshasas to join the council of Chandragupta. Chanakya consistently woos a bitter adversary, to his point-of-view because of his talent as a worthy Prime Ministerial successor. That should be the driver motivation for political parties when trying to bring in able candidates from rival camps during or after elections. The Arthashastra warns: “The greatest threat to a king is from his counsellors. The greatest threat to its citizens can be posed only by their king.” If you replace the ‘king’ with the prime minister or the president, the argument holds good even today.

Exercising power without getting entrapped by its failings is not easy, and it’s but natural for the human to err. But if one follows the Arthashastra model – ‘the end good could justify tough means, so long as the end good is justifiable enough’.

The Indian electorate, whenever offered a direct opportunity to choose its Prime Minister, has always sought and aspired for that maximum leader in the Chanakyan model, with the stronger nationalist enjoying an edge. Larger-than-life leader Prime Ministers like Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, Atal Behari Vajpayee and Narendra Modi today – fed and feed an expectation built into a consciousness born of years of experiencing personality-driven monarchical governance models. Those who didn’t, despite their valuable stint and admirable capabilities like P.V. Narasimha Rao or Manmohan Singh failed to capture immediate national imagination. However, Chanakya’s functioning style of decisive governance driven by ruthless pragmatism towards the achievement of what they believed and envisioned to be in the best interests of the nation in post-independence India has been replicated, if only, by Indira Gandhi and Narendra Modi in both his innings as Chief Minister and Prime Minister to lend their seemingly autocratic state-sanctioned arbitrations a sense of timely necessary corrections; hence culling spontaneous majority adoration. It’s silly to expect Indian political parties, their workers and voters to give up that subconscious conditioning of centuries and expect people to put faith in a leaderless opposition – small or big – because though ‘democracy’ as a political system may be a western idea import, it’s adaptation and manifestation the Indian way is guided more by the practical experimentations with Chanakya’s ‘tested’ neetis than the theoretical idealisms of Plato’s ‘aspired’ republic.

The writer is an author, critic, filmmaker and associate professor at Jain University, Bengaluru

Contact: criticpiyushroy@gmail.com

Comments are closed.