Dadasaheb Phalke: The One-Man Miracle By Piyush Roy

How the filmmaker set India’s moviemaking template

Only half of India’s first ‘indigenous/desi’ film, Raja Harishchandra survives. The industry it spawned is an amalgamation of myriad world cinema influences today, but the debut feature from India’s first auteur-filmmaker Dhundiraj Govind Phalke or Dadasaheb Phalke calls for a fresh review on cinematic merits and pioneering influence in setting an ‘Indian moviemaking’ template.

Filmmaking began in India by the turn of the 19th century, with Shree Pundalik, a full feature by Dadasaheb Torne, releasing in 1912. Yet, Raja Harishchandra was the first to be ‘acted, directed and produced’ by an all-Indian team. Shree Pundalik, a recorded stage play, filmed by a British cameraman, processed in London, wasn’t swadeshi enough. Phalke, in sync with the prevailing mood of identity and freedom, proudly asserted, “My films are swadeshi in the sense that the capital, ownership, employees and the stories are swadeshi.” (Navayug, September, 1918).

Phalke’s trigger was a chance viewing of a silent classic, The Life of Christ, in 1911. He wrote: “While The Life of Christ was rolling fast before my physical eyes, I was mentally visualizing the gods, Shri Krishna, Shri Ramachandra, their Gokul and Ayodhya…” (Navayug, November, 1917). From Raja Harishchandra to Phalke’s last and only talkie, Gangavataran (1937), his 100-plus films drew plotlines from the epics, the Puranas and Sanskrit literature.

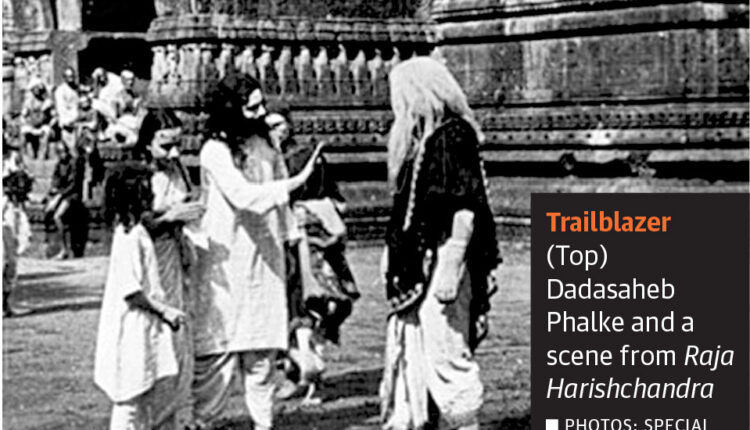

The king of Ayodhya, Harishchandra (Dabke), is famous for his adherence to truth in all circumstances. One day, while on a shooting expedition, he accidentally spoils a yagna by sage Vishwamitra (Sane), who decides to put his famed reputation to test. Obstacles are created resulting in the loss of kingdom, the selling of his wife, Taramati (Salunke), and only child, Rohidas (Bhalchandra). The king becomes a pauper and works in a graveyard burning dead bodies for survival. His separated wife and son too go through innumerable hardships resulting in the death of the prince, but the couple never forsakes the path of truth. In the end, redemption is delivered by Shiva, and his kingdom and son restored.

Special effects and action

A silent film doesn’t have the luxury of elaborate conversations. Naturally, action takes over to keep the drama going. Phalke shoots most of his action outdoors; he goes the whole hog — a long trek on undulating landscapes, crowds in motion, chaos in a hermitage, women in a pond splashing water, scenes of violence — all in a span of 20 minutes. The collage of outdoor sequences highlight Phalke’s understanding of cinema’s signature differential as a narrative medium of halti chitra (moving visuals).

George Mêliés, the father of special effects in French/ European cinema, had a studio and trained hands to realise his vision. The ‘Mêliés of India’ just had himself and his imagination. Yet, he never tired of introducing new ‘tricks’, as special effects were called then. Raja Harishchandra’s first trick moment is when Harishchandra is conned to save three vices, portrayed as girls, being burnt in a sacred altar by Vishwamitra. Their bodies, waist upwards in flames, are strategically covered by the sage’s silhouette. The other ‘trick’, seen in salvaged remnants of the film, is the sudden appearance and disappearance of Shiva in the climax scene.

The film also has some beautiful landscape cinematography and well-lit interior shots. The London press noted that “from a technical point of view, (Phalke’s films) are surprisingly excellent,” when he took his first three films there in 1914.

With the camera remaining fixed, the amount of action and movement packed into a single scene showed the meticulous planning that would have gone into their composition. For instance, the scene of Harishchandra’s departure, a single take in his palace compound, begins with the prince enjoying a moment on the swing, followed by Vishwamitra’s arrival, and Harishchandra’s handing over his crown to him. Next, the angry sage forces the king and his family to give him their regal finery and change into ordinary robes. It ends with the king’s exit and the sage now rollicking on the swing with the crown.

Such a busy, long take with 20-plus characters acting in logical chronology, with no change in the camera’s frame of view, would be celebrated as a ‘technical achievement’ today! The screenplay guiding the visual drama in Raja Harishchandra was ahead of its times in comparison to many subsequent silent Indian classics, where all the action was mostly limited to a character’s entry and exit.

Made with hand-driven machines, sans proper studio facilities, with inexperienced technicians in every department of filmmaking, the theatrical release of Raja Harishchandra on May 3, 1913 in Bombay was nothing short of a one-man miracle. “I had to teach acting, write the scenarios, do the photography and actual projection too. Nobody knew anything in India about the industry in 1911,” Phalke later reminisced. Thankfully, a century-and-a-decade hence, wherever his restless soul maybe, this is one ‘father’ who cannot complain of unworthy offspring.

https://www.thehindu.com/entertainment/movies/dadasaheb-phalke-the-one-man-miracle/article35224204.ece

Comments are closed.