Drawing With Light

SEBASTIAO SALGADO is an eternal optimist, despite witnessing and documenting a near half-century of brutality, writes PIYUSH ROY

There are good films. There are great films. And then are those rare few that can change your life and thinking. You feel privileged to have witnessed such a film. You may also feel cathartic. It could be about a truth, a beauty, a life, a lament or a celebration.

But you rarely come out as the same person, who had gone into the theatre.

Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribeiro Salgado’s documentary, The Salt Of The Earth, on Brazilian photographer and humanist, Sebastiao Salgado, is one such film. On the face, it’s just another collage of a career in photography, with the photographer telling the story around and about his images. But as the bio-documentary unfolds, you are enriched with insights, not only on life in the 20th century but certain universal truths about the human nature and its existence, along with a surprise revelation or two about you, which may not be flattering.

Salgado’s World

The film begins with Wenders, talking about his introduction to the ‘black and white world of Salgado’. Two photographs were encountered in an exhibition — one, a solo portrait, and the other of an individual amidst a sea of humanity. The first profiles a blind woman. Wenders could never forget its poignant capturing of unwept tears in blank eyes. A copy of that photo has been adorning his study since.

The other, was that of an askance miner among a sea of ‘adventurers’ in a gold mine called Serra Pelada, in Salgado’s birth country, Brazil. A profound sight, Salgado describes the image as one that could have been from the making of any of human history’s grand projects — the Pyramids of Egypt, King Solomon’s mines….Tales of grit and greed, adventure and exhaustion, death and dreams of subjects, who would never remain the same, after touching or having been touched by gold.

About the miners, he says, “All men, when they begin to touch gold, they do not return….”

About ‘violence’, which he has recorded from genocides in Rwanda and Sudan to carnages in Eastern Europe or the wasted oil fields of Kuwait set ablaze by fleeing Iraqi forces, he feels, is ‘contagious’ in its nature and attraction. Documenting devastation, across continents, the film reveals the humans’ tremendous appetite for destruction. “Violence and brutality are not a monopoly of distant (or poor, underdeveloped) countries. Humans are terrible animals,” says Salgado, while talking about an image from Yugoslavia’s ethnic strife that captures the horrors of war on the face of a child behind a bus window, through which a bullet had just passed and killed a copassenger.

Migration, refugees, wars, famine, genocide and exodus are recurring themes explored by this United Nations’ feted photographer, who has witnessed and preserved some of the major earth events of our times. These long-term, self-assigned projects have resulted in acclaimed photo books — The Other Americas, Sahel, Workers, Migrations and Genesis — that feature hundreds of images each from all around the world. Salgado’s four decade- old canvas encompasses a grand spread of 120 nations.

But his bequest is not of lament alone. In October 2007, he showcased photographs of coffee workers from India, Guatemala, Ethiopia and Brazil to raise awareness on the origins of the popular drink. His love for humanity is the grand connecting narrative in all his projects; even famines and migrations, which while getting him to capture their frailties, also have him looking for hope and courage in the most unlikely contexts. This is evident in the image of a mother and a child in banter, unworried, even if only in the moment of capture, amidst refugees taking a break, in a march of mass migration. The picture is also one of Salgado’s personal favourites.

What is it about his pictures that make them special, instantly connecting, unforgettable, and universal? It is in the absoluteness of a fact, oozing literally, from his every frame — Salgado’s pictures care about his subjects.

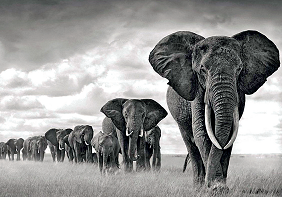

The brief, on his multination project, Workers, for instance, reads: ‘A tribute to men and women who built our world’. Care reflects, even in the case of occasional wildlife photography; from his life’s last major photo project (2004-2011) capturing unblemished faces of nature and humanity, titled, Genesis. It consists of a series of photographs of landscapes and wildlife, along with human communities, who continue to live in accordance with their ancestral traditions and cultures. The project was conceived as a potential ‘pathway for humanity to rediscover itself in nature’.

Today, the 74-year-old Salgado and his wife, Lelia, spend most of their time nurturing a live project started in the 1990s, involving the restoring of a small part of the Atlantic forest that has successfully turned a tract of barren land off his hometown into a nature reserve for reforestation, conservation and environmental education called Instituto Terra.

Looking at his audience, from in front of the camera for a change, Salgado at the beginning of The Salt Of The Earth, explains the origin of the naming of his calling, in two Greek words, photo and graphein. These mean, ‘light’ and ‘writing or drawing’ respectively. “So, a photographer is literally someone drawing with light. Someone who writes and rewrites the world with light and shadow.” And in the case of Sebastiao Salgado, also an eternal optimist, who after witnessing and documenting a near half-century of brutality, along with beauty, believes that ‘death is just a continuation of life’. The writer is a critic and associate professor at Liberal Studies, Jain University, Bengaluru

Film:The Salt Of The Earth (2014)

Duration: 110 minutes

Language: Portuguese,French, Italian and English

Director:Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribeiro Salgado

Cast: Sebastiao Salgado,Wim Wenders and Lelia Wanick Salgado

Music: Laurent Petitgand

Comments are closed.